Peripheral Lesions Associated with an Increased Risk of Diabetic Retinopathy Progression

The increasing use of ultra-widefield (UWF™) retinal imaging is giving the optometric and ophthalmic communities a more comprehensive diagnostic platform as well as a powerful tool to explore the pathology and progression of a broad range of retinal diseases and conditions.

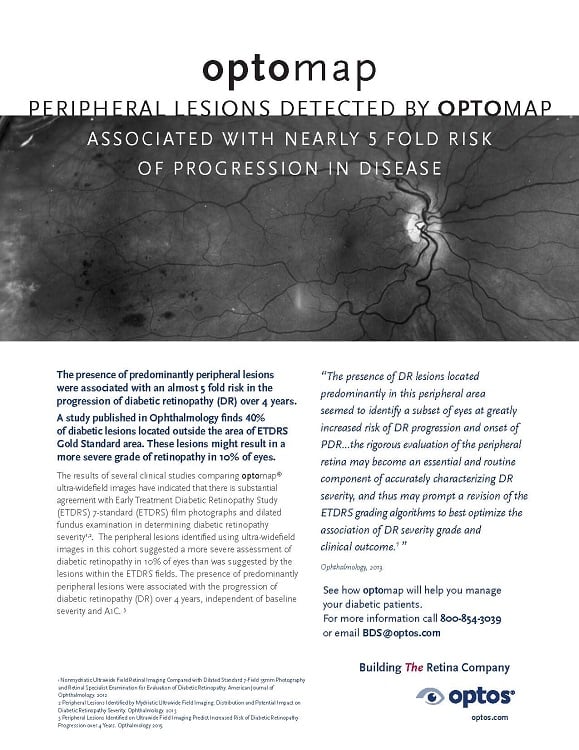

Peripheral lesions detected by optomap associated with a nearly 5-fold risk of progression in disease

The diagnosis and study of diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of several fields where UWF imaging is having particular impact. It’s estimated that over 400 million people across the globe are afflicted with diabetes and that number is expected to increase to over 600 million by 2040. As many as a third of those diagnosed with diabetes will also develop DR[1], a leading cause for blindness in adults. This growth is spurring the need for improved techniques for DR screening and diagnosis.

About UWF Retinal Imaging

Ultra-widefield imaging is performed by a specially designed scanning laser ophthalmoscope (SLO) that generates a high-resolution digital image covering 200° (or about 82%) of the retina. The SLO simultaneously scans using two low-power lasers (red and green) that enable high resolution, color imaging of retinal substructures. The scan is produced in a single capture without pupil dilation. Along with UWF color imaging, the technology can also support ultra-widefield fluorescein angiography (FA), UWF fundus autofluorescence (FAF), and UWF indocyanine green chorioangiography (ICG).

Conventional 7 standard field (7SF) ETDRS photographs produce a comparatively narrow view (45° or less) of the center-portion of the retina. Peripheral portions are not imaged.

Tracking Diabetic Retinopathy Progression with UWF Retinal Imaging

Multiple studies have demonstrated that UWF retinal imaging provides a DR screening and diagnosis platform that’s comparable or better than conventional 7SF techniques. Practitioners have also noted that UWF imaging capture and review is faster and more efficient. In addition, the ability to image a larger area of the retina is offering diagnostic data not previously available.

One recent study suggests peripheral imaging of the retina can provide data that can be used to evaluate the risk of subsequent DR onset or progression. This work, undertaken by a team from the Joslin Diabetes Center, examined patients using both conventional 7SF ETDRS and UWF retinal imaging techniques. As part of baseline data collection the team characterized what they defined as “predominantly peripheral lesions”, or PPLs. These were DR lesions found on the UWF images that were located to a greater extent outside of the standard ETDRS fields. The study’s goal was to determine if these PPL’s could provide any added value in predicting the onset of DR or its progression.

A hundred diabetic patients participated in the study and included individuals with a range of no DR (ETDRS level 10) to high-risk PDR (ETDRS level 75). All were examined at the start of the study with 7SF ETDRS photographs and UWF retinal scans. They were re-examined approximately four years later with ETDRS. ETDRS photographs only were used to grade baseline and follow-up DR severity. To characterize the severity of the PPLs, the authors mapped their location using defined peripheral fields.

The study’s findings included:

- In those eyes with baseline grading indicating no DR, those with PPLs uncovered during baseline UWF imaging were 2.5 times more likely to develop DR four years later as compared to those with no PPLs (83% versus 33%).

- PPLs were associated with accelerated DR progression. Eyes with no proliferative DR at baseline but with any PPLs had a 3.2-fold increased risk of 2-step or more DR progression. These eyes had a more than 4X-increased risk (25% versus 6%), for progression to proliferative DR compared with eyes without PPLs.

- The severity of PPLs was also associated with accelerated DR progression. After four years those eyes with PPLs in multiple peripheral fields were statistically more likely to exhibit the onset of proliferative DR and 2-step or more DR progression.

- No statistical relationship was found between the presence of PPLs and the development and progression of macular edema.

The study’s authors noted that the role of PPLs in the onset of diabetic retinopathy was still not understood, and that the predictive value of PPLs needed confirmation in a larger study. They also observed that if the predictive value of PPLs is confirmed, it has the potential to change diagnostic standards. UWF imaging of peripheral lesions could provide more comprehensive, predictive diagnostic screening and in turn offer the potential for improved clinical outcomes.